Nem "kampányolok" én, csupán felhívom a figyelmedet egy történelmi tényre. Ha szeretnéd, ennek bármely enciklopédiában utánanézhetsz. A maszoréta szöveg előtt nem volt magánhangzó jelölés a héberben, és ezt a maszoréták illesztették be, évszázadokkal azután, hogy a templom megsemmisült.

"Akkor Jahovah lenne, nem Jehovah." - Na, ebből látszik, hogy nem ismered a héber hangtant, hogy van amikor a szerkezetből következik a hangeltolódás, nézd csak:

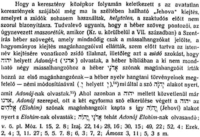

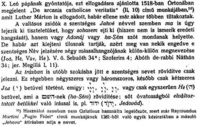

"The Hebrew term יְהֹוָה has the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי (adonai). Using the vowels of adonai, the composite hataf patah ֲ under the guttural alef א becomes a sheva ְunder the yod י, the holam ֹ is placed over the first he ה, and the qamats ָ is placed under the vav ו, giving יְהֹוָה (Jehovah). When the two names, יהוה and אדני, occur together, the former is pointed with a hataf segol ֱ under the yod י and a hiriq ִ under the second he ה, giving יֱהֹוִה, to indicate that it is to be read as (elohim) in order to avoid adonai being repeated.

The pronunciation Jehovah have arisen through the introduction of vowels of the qere—the marginal notation used by the Masoretes. In places where the consonants of the text to be read (the qere) differed from the consonants of the written text (the kethib), they wrote the qere in the margin to indicate the desired reading. In such cases, the kethib was read using the vowels of the qere. For a few very frequent words the marginal note was omitted, referred to as q're perpetuum. One of these frequent cases was God's name, which was not to be pronounced in fear of profaning the "ineffable name". Instead, wherever יהוה (YHWH) appears in the kethib of the biblical and liturgical books, it was to be read as אֲדֹנָי (adonai, "My Lord [plural of majesty]"), or as אֱלֹהִים (elohim, "God") if adonai appears next to it. This combination produces יְהֹוָה (yehovah) and יֱהֹוִה (yehovih) respectively. יהוה is also written ’ה, or even ’ד, and read ha-Shem ("the name")."

Az ún. "mai héber szövegek" nem mások, mint a maszoréta szövegek, ezért nem véletlen, hogy az a központozás szerepel benne. Kérdezz meg bármely tetszőleges rabbit, hogy mi ennek a története, a zsidó lexikon is azt igazolja, amit én mondtam. Nem azt mondtam, hogy azért nem ejtik ki, mert sérti a fülüket: szövegértéseddel bajok vannak. Azt mondtam, hogy az Adonáj magánhangzóit azért illesztették bele, hogy az olvasó egyből kapcsoljon, hogy ott Adonájt kell mondani. Ezt hívják a zsidók Qere és Ketiv írásmódnak. A babiloni fogság előtt csakugyan kiejtették a tetragrammát, de nem úgy, mint "Jehova", hiszen ez egy késő-középkori tévedés, hanem max úgy hoggy Jáhvé. Mellesleg a fogság után már nem ejtették ki, és Istennek egy szava sem volt ez ellen: ezek szerint nem üdvösségi kérdés ennek a "használata" - ez csak JT-inek vált egyik vesszőparipájává.

"Semmit nem ér az általad kihangsúlyozott profizmus és a tanultság, ha valaki szellemileg vak." - Semmit sem érnek az olyan vallásoskodó alibiszövegek, amely minden érdemi ellenvetést azzal intéz el, hogy aki mást gondol, mint az Őrtorony az szellemileg vak. Mellesleg az Őrtorony nem is mondja azt sehol, hogy a maszoréta központozás az ősi kiejtést idézné: ők azt hangsúlyozzák, hogy azért ragaszkodnak a Jehova kiejtéshez, mert az "bevett", "megszokott", "elterjedt" stb. nem pedig azért, mert helyes. Magyarul a hagyományra hivatkoznak.